Reason to increase:

The under-investment in a recession will result in a shortage of capital stock to replace depreciation of capital. This shortage of capital stock will translate into negative and reducing inventory levels, which signal to producers to increase investment and capital stock, leading to increased use of resources and eventually to full employment. It is likely that the shortage of capital will make capital scarce- and thus increase the marginal efficiency/cost of capital. Another way of illustrating this is to shift the investment demand curve to the right; this results in upward pressure on real interest rate as well.

Right now the US is relying on an infinite source of capital inflow to fund its investment-savings shortfall. The escalating US debt may give rise to concerns of the ability of the Government to rein in deficits and reduce debt over time via reduced outlays and increased taxes. The removal of capital inflows can occur as investors lose confidence in US assets, and this capital flight will reduce the supply of capital and raise the real interest rate.

The combined effects of a falling dollar and rising real interest rates are tantamount to disaster, and many of the currency crises in Latin America, the Asian financial crisis, followed this path. To make it worse, nominal interest rates were in fact increased in these countries to maintain capital inflows- which futher worsened the domestic economy- fuelling doubts about the soundness of the economy- leading to more capital flight- forcing further interest rate increases...and this adverse feedback loop continued until the currency plunged and the economy underwent a prolonged recession. Now, this is unlikely to occur in the US, given that the source of capital inflows come from countries that require US demand to drive their export-sectors (China, Japan, for example).

Reason to decrease:

Well, we know that the collapse in risk tolerance has led to a widespread increase in liquidity and risk premia, as lenders have to hedge against the risk of default. The process of deleveraging has led to a widespread fall in asset prices, as expectations of bankruptcy impacts upon the asset values of banks, where people fear the fact that a bank sells assets is due to the fact that they are ‘lemon assets’. Now upon recovery, it is obvious that the healthy flow of credit will result in the reduction in credit spreads, with reduced risk premia.

Given that deflationary expectations are emerging, as unemployment increases past the natural rate and output growth falls below potential, this is increasing current real rates. Over time, as the economy begins to recover, the inflationary expectations will increase, lowering real rates for a given nominal rate.

How to deal with the opposing forces on real interest rates? The transition from short-run to long-run:

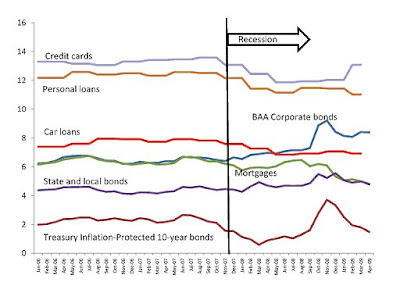

Typically real interest rates are lower in recessions and higher in a boom-time. This is because in a boom time there are more investment projects, more investment demand, which tends to put upward pressure on the real rate, as the marginal product of capital increases. The only exception I suppose happens when a systemic banking crisis causes a contraction in credit, and rising liquidity and risk premia on private market assets mitigate the necessary cash flow to keep corporate investment going. This is particularly evident in the following graph, which shows little change in mortgage and business rates despite excessive easing by the Fed:

(Graph from Woodward and Hall blog). This clearly shows that at current the credit crunch is leading to a rise in nominal and real interest rates, which are a principal reason for constraining investment and leading to the insufficient demand at present. On the face of this we would expect that real interest rates to lower as the credit crunch abates.

(Graph from Woodward and Hall blog). This clearly shows that at current the credit crunch is leading to a rise in nominal and real interest rates, which are a principal reason for constraining investment and leading to the insufficient demand at present. On the face of this we would expect that real interest rates to lower as the credit crunch abates.

Another aspect is trying to distinguish between real rates and natural real rates persay. For example, at current we suffer from a situation of the real rate being above the natural rate of interest- this correlates to the excess supply of savings as households and firms are deleveraging. There is little doubt that the natural real rate is -ve at the moment, this is the real rate required to restore full employment. Studies conducted by the Fed and Goldman Sachs determine the nominal interest rate required at current is -5/-6%, as determined by a Taylor rule:

(Above graph from Krugman blog, study by Goldman Sachs). There is little doubt that if the natural real rate is seen as -ve at current, then it must move upwards as the economy recovers.

(Above graph from Krugman blog, study by Goldman Sachs). There is little doubt that if the natural real rate is seen as -ve at current, then it must move upwards as the economy recovers.

One last point is that, as I have mentioned in previous posts, this crisis is due principally to a global savings glut- which has fed US demand for funds and led to very low interest rates in the US. This was partially due to the fact that investment demand was low following the dot-com bust, and interest rates went to fundamentally unsound levels- fuelling a residential investment boom. Now nominal interest rates remain low, and real rates are likely to remain low once the credit crunch abates- simply because households and firms are in the process of reaching +ve equity, and firms, rather than re-investing cash flow, are likely to use it to pay debt. I predict this insufficient investment will persist until firms and households have delevaraged, and private debt to GDP ratio is more sound. Once physical capital has depreciated and requires replacement, once house prices start trending upwards, it will provide an impetus for physical and residential investment, and increased investment demand for loanable funds will raise real and nominal rates.

Whether this process described above will occur will depend on the persistence of capital inflows into US, which in turn is based on confidence in the $US and whether foreigners believe US debt is guaranteed and will be non-monetised. I believe that the capital inflows into US will reduce over time- as developed countries like China and India open their capital accounts- we should expect higher rate of return in these countries, and a reallocation of capital inflows into these countries. However I doubt that such capital flight from the US will be drastic enough to increase real interest rates in the US, and I do not forsee such a reallocation of capital inflows in the near future.

A great policy lesson from this crisis is that excessively low real rates can cause bubbles. The problem is keeping interest rates low for a prolonged period of time. Unfortunately a big fallback of inflation targeting is that interest rates that are consistent with a stable inflation are inconsistent with asset prices. In the circumstance that asset prices are driven by speculation, then real rates should be increased to curb the increase in asset prices, and ensure they grow at a more sustainable rate. Unfortunately, given underlying inflation is stable, monetary policy becomes insensitive to asset price bubbles- and in the leadup to the housing bubble- the Fed and Treasury encouraged residential investment and ignored the possibility of a house price collapse.

I think the residue from this crisis will result in a more protracted form of lending and securitisation as financial instituions become more risk-averse. This will constrain lending and put further upward pressure on real interest rates. In conclusion, I believe that real interest rates will remain low during the recession (but still above the equilibrium/natural rate of interest), but there are good reasons to believe that real interest rates will rise in the long-run, in the recovery-phase and beyond.

To finish, let me illustrate my short-term/long-term analysis of real interest rates via a graph:

The blue curve is for the natural real interest rate, the black curve for the real interest rate. Note that the period of under-investment corresponds to the period directly after the credit crunch has abated, and is the period of the recession where private sector borrowing is still reducing or below the level required in the recovery phase. I mark the recovery phase as the period in which both the real rate and natural rate of interest are increasing, however the magnitude of this increase is uncertain.

Notice that the reason why the real rate cannot converge to the natural rate during the recession is because of the 0 lower bound on nominal rates! Also, note that I assume that real rate converges to natural rate as economy approaches full employment.

where t is the marginal tax rate. Note that the simple multiplier can be used because interest rates are assumed to be fixed (a fair assumption) With estimates such as MPC=0.5, and t=1/3, we obtain a multiplier of 1/(1-(1/3)) = 1.5. This means for an increase in $100B of government spending, we have an increase of $150B in GDP. From the $150B increase in GDP $50B is collected in taxes (due to t=1/3), and a ‘bang for buck’, that is, the amount of increase in GDP per dollar of the future deficit is 3 (As the future deficit is $50B, and 150/50=3). Thus the recovery of half of the lost revenue comes via increased incomes resulting in increased taxation revenue. It is interesting that dynamic scoring increases the gap between those who prefer infrastructure spending and those who prefer tax cuts. According to tax cuts, the multiplier is ,

where t is the marginal tax rate. Note that the simple multiplier can be used because interest rates are assumed to be fixed (a fair assumption) With estimates such as MPC=0.5, and t=1/3, we obtain a multiplier of 1/(1-(1/3)) = 1.5. This means for an increase in $100B of government spending, we have an increase of $150B in GDP. From the $150B increase in GDP $50B is collected in taxes (due to t=1/3), and a ‘bang for buck’, that is, the amount of increase in GDP per dollar of the future deficit is 3 (As the future deficit is $50B, and 150/50=3). Thus the recovery of half of the lost revenue comes via increased incomes resulting in increased taxation revenue. It is interesting that dynamic scoring increases the gap between those who prefer infrastructure spending and those who prefer tax cuts. According to tax cuts, the multiplier is , which for MPC=0.5 and t=1/3 is 0.75. Furthermore, given the example of a $100B tax cut, we have an increase in GDP of $75B, and a $25B taxation revenue gain. Thus, the ‘bang for buck’ is only 1, compared to 3 for Government purchases. What this example shows, is that even with a low MPC, Keynesian theory supports deficit spending as the burden on future debt is minimised via taxation revenue recovery from increased incomes.

which for MPC=0.5 and t=1/3 is 0.75. Furthermore, given the example of a $100B tax cut, we have an increase in GDP of $75B, and a $25B taxation revenue gain. Thus, the ‘bang for buck’ is only 1, compared to 3 for Government purchases. What this example shows, is that even with a low MPC, Keynesian theory supports deficit spending as the burden on future debt is minimised via taxation revenue recovery from increased incomes.

To understand whether protectionism makes sense, we need to look at the Balance of Payments Equilibrium equation, or BP curve. This curve models the pairs of income and interest rates required to fulfil the following condition:

To understand whether protectionism makes sense, we need to look at the Balance of Payments Equilibrium equation, or BP curve. This curve models the pairs of income and interest rates required to fulfil the following condition:

It is important to note that the differential X-M is the same, which means that both the volume of imports and exports has dropped by equivalent amounts. Consequently, protectionism does not achieve its desired goal of achieving greater effects of fiscal stimulus- as the gains of reduced imports come at the expense of reduced exports.

It is important to note that the differential X-M is the same, which means that both the volume of imports and exports has dropped by equivalent amounts. Consequently, protectionism does not achieve its desired goal of achieving greater effects of fiscal stimulus- as the gains of reduced imports come at the expense of reduced exports.