"Policy Responses to the Global Financial Crisis. Many countries around the world are responding to the global financial crisis and the associated economic downturn with stimulatory fiscal and monetary policies. Discuss the appropriateness of these policy responses, and the extent to which the exact nature of these responses might matter. Essays should provide an overview of the theoretical arguments and also briefly consider the evidence, including the approaches adopted by different countries in the past"

This essay was a great opportunity for me to use some of the knowledge I have gained over the past year or so. Unfortunately, my chances of winning the competition are very slim. Reasons are:

i) The suggested word count for the essay is 2000 words. My essay word count is 3700!

ii) My primary source of information have been the blogs I have been reading on a regular basis. I'm not sure whether this source is acceptable in a professional essay. It is just that alternative sources, like IMF reports, are extremely tedious to read, as well as serious academic papers on the crisis.

iii) The question is very general, and it does not refer to a particular country one should look at. In consequence I have focused primarily on the US policies to deal with the current crisis, and in looking at past examples I have looked at Japan. I'm not sure whether singling out a country for all your examples is optimal.

iv) Last, but not least, is that to my knowledge I made two typos which said the contrary of what I intended to say. I corrected it in this essay, but I hope it doesn't cost me so much.

I think for my efforts I deserve a certificate of commendation, but it is not up to me to decide. In any case I enjoyed writing this essay, and it is probably my best blog-post to date in terms of synthesising the two main topics of monetary and fiscal policy.

Figure 1: Global Expansionary Monetary policy

Koo,2009

The question is, has this been effective in reducing interest rates to businesses and households? The problem is, because of frictions in credit markets, financial institutions are simply not passing on rate reductions on to their customers. This is in large part due to the high credit and liquidity risk that exists in interbank markets, that is, the majority of a bank’s source of funding is lent at much higher rates than Central Banks’ rates. This is represented by the Libor-Ois spreads.

Figure 2: Credit spreads for Major Advanced Economies

Battellino,2009

This is crucial to understanding why a whole range of rates have dropped very marginally, and in the case of corporate bond rates, have risen!

Figure 3 Credit Crunch affecting interest rates to households and firms in US

Woodward&Hall,2009

It is clear that on the Monetary Policy front, merely cutting the cash rate towards 0 has not been enough to stimulate the economy. Thus there has been a turn to ‘unconventional monetary policy’ in this crisis.

It is clear that on the Monetary Policy front, merely cutting the cash rate towards 0 has not been enough to stimulate the economy. Thus there has been a turn to ‘unconventional monetary policy’ in this crisis. The Liquidity Trap: How conventional Monetary Policy loses traction

It is established that despite near 0 interest rates, there are still additional policies Central banks can use. One such response that has been used is Quantitative easing, which are attempts to increase the size of the Central Bank’s balance sheet by purchases of securities, and crediting the payments to reserve accounts at banks. These are regular open market-operations, with the difference being that interest rates are now constrained by the 0 lower bound.

In normal times the Central Bank purchases of securities puts upward pressure on the price of bonds, lowering interest rates and the cost of funding in credit markets. The injection of reserves into banks will be lent out at lower interest rates, and this new cash inflow to the economy will stimulate economic activity and make the final money supply increase much larger than the initial injection of High-Powered (HP) Money.

Figure 4 HP money growth deviates from broad Money Supply Growth in Japan

Koo,2009

Therefore the success of Quantitative easing is contingent on the extra reserves being lent out. Unfortunately there is no longer this mechanical connection between HP money growth and broader measures of the money supply. This is apparent in Japan's 'lost decade', which was the first experiment of Quantitative easing (Koo,2008).

As Japan’s recession began, a divergence between HP money growth and broad measures of the money supply/domestic credit growth became apparent. The problem is that the excess reserves are increasing due to Banks requiring excess reserves as a safety net to repay debt, to raise capital, and from pure credit rationing to consumers and firms. A large increase in deposits at the Central Bank (excess reserves) is the case for the US, Japan, EMU and England (Batellino, 2009).

Figure 5 Excess reserves increasing in major advanced economies

Battellino,2009

Given that money supply creation is dependent on lending excess reserves, this increase in the effective reserve ratio means the money multiplier, which measures the increase in money supply due to a $1 increase in HP money, is now less than 1 in the US.

Figure 6 Falling Monetary Multiplier in US

Mankiw, 2009

The problem of conducting quantitative easing is that when interest rates are so low, money and bonds become near-perfect substitutes. What happens is that the purchasing of securities by the Central Bank and the corresponding injection of reserves into banks has no real effects, as reserves are risk-free assets that are comparable with bonds. This is the theory of 'liquidity preference', put forward by Keynes to show how a 'liquidity trap' constrains lending, as banks are willing to sit on a pile of reserves at such low rates, as they are more liquid and earn the same yield as bonds.

The problem of conducting quantitative easing is that when interest rates are so low, money and bonds become near-perfect substitutes. What happens is that the purchasing of securities by the Central Bank and the corresponding injection of reserves into banks has no real effects, as reserves are risk-free assets that are comparable with bonds. This is the theory of 'liquidity preference', put forward by Keynes to show how a 'liquidity trap' constrains lending, as banks are willing to sit on a pile of reserves at such low rates, as they are more liquid and earn the same yield as bonds. Using the IS-LM model, the liquidity trap can be represented by an infinite interest elasticity of money demand at low interest rates, and a horizontal LM curve. The result is that any increase in the Money supply equilibrates Money demand without a lowering of interest rates (as interest rates are constrained by the 0 lower bound). Thus a rightward shift of the LM curve leads to no effect on equilibrium income.

Figure 7 The liquidity trap: Conventional Monetary Policy becomes ineffective

A creative solution: Charging Banks on holding excess reserves

A policy conundrum at present in the US is the Fed’s paying of 0.25% interest on excess reserves. The main reason for such a policy is to maintain a floor on the Fed Funds rate, as Banks will not lend to each other at rates below the rate at which their risk-free reserves earn. However, given that the economy is suffering from a lack of availability of credit, it makes more sense for the Central Bank to tax excess reserves (Woodward&Hall, 2009) This would increase the incentive to lend excess reserves, and we would obtain a stronger linkage between HP money growth and broader money supply growth.

Such a policy would be in line with a Taylor rule (A Monetary rule which calculates interest rates as a function of deviations of inflation and output from their natural rates), which the Federal Reserve calculates at roughly –5% for 2009 (Macroblog,2009)

Figure 8 Taylor Rule projections for Fed Funds rate in US

Macroblog,2009

Such a policy could give impetus to Quantitative Easing, which has been ineffective in stimulating the economy.

Such a policy could give impetus to Quantitative Easing, which has been ineffective in stimulating the economy.

Further Innovations in Unconventional Monetary Policy in 0 lower bound conditions:

Figure 9 The Burgeoning Fed’s Balance Sheet

Woodward&Hall,2009

Monetary Policy in the US has involved diversifying and changing the composition of the Central Bank balance sheets. Looking at the above balance sheet, instead of purchasing treasury securities (conventional monetary policy), the majority of their purchases are private securities (classified as ‘other assets’). The intention is to create price stability in a range of asset markets, by driving their price up and moderating their yield, with the additional advantage of taking these assets off their balance sheets and supplying the much-needed liquidity. This has been termed ‘credit easing’ by Bernanke (Battellino,2009).

Whether ‘credit easing’ has effect is uncertain. One critique is that it may not change the price of assets enough to create a new equilibrium at which investors are confident in the value of private assets. This is because the markets for private assets are of a much greater magnitude than the $2 Trillion worth of private assets bought by the Fed, and the increase in demand is not enough to significantly increase the price of such assets. The Fed is also taking the role of a private bank- by investing in assets with much higher risk than its non-risk counterpart treasury bills (Krugman,2008).

Another unconventional monetary approach in 0 lower bound conditions is to invest in longer-term treasury bonds. The idea is that, if yields on short-term treasury securities have bottomed out, then it may be worth reducing yields on long-term bonds, trying to create low interest rates for a prolonged period of time. By flattening the yield curve, this can help in raising inflationary expectations and hence reducing the real rate, which will help ease credit conditions and induce consumption and investment (Krugman,2008).

Unconventional monetary policy is seen as essential to prevent ‘adverse feedback loops’ (Mishkin, 2009) in which, had these unconventional balance sheet operations not been conducted, there would be increased uncertainty in asset values, causing further contraction in credit, more uncertainty in asset values, leading to a vicious cycle of falling asset prices and confidence. There is no doubt that part of the reduction in credit spreads since the sharp increase in September 2008 is due to unconventional Monetary Policy. However the main problem is that Monetary Policy has lost traction in controlling economic activity and inflation, and this has required the increased involvement of fiscal policy.

Fiscal Policy Responses in the area of Financial Stability:

A major fiscal measure to stabilize financial markets is the advent of ‘Government guaranteed’ deposit insurance. The idea is that a Bank is much more likely to obtain funds if their debts are covered by the Government. Even in Australia, where Banks have managed to retain their AA ratings, the majority of bond issuance has required deposit insurance (Debelle,2009).

Figure 10 The effectiveness of deposit insurance for Australian banks’ borrowing

Debelle,2009

The main fiscal measure in this crisis has been capital injections. This is in light of the fact that in a systemic crisis, with little demand for funds, Banks can only be recapitalised via a capital injection (Koo, 2009). Capital injections have come in the form of nationalization of banks as in the UK, in which there is a large equity stake in the Bank, or more subtle forms such as the ‘TARP’ program in the US, which are aimed at removing ‘toxic assets’ of Balance sheets.

The problem with measures such as the TARP is that they may be funding institutions only to the point that they can cover all losses to debt holders, but only barely. Subsequently, ‘stress tests’ used to determine the amount of capital required is only to sustain solvency, rather than a full-recapitalisation (Woodward&Hall,2009). Much of the hope of US financial stability policies rests on the idea that assets are wrongly priced and that there is an expectation that once the ‘crisis of confidence’ wanes asset prices will increase and banks’ balance sheets will begin to look healthy again.

Avoiding bankruptcy is useful in a systemic crisis, as evidenced by how influential the failure of an institution ‘too big to fail’ such as Lehman Brothers was. In that case, it is useful to consider the idea of the ‘Good Bank, Bad Bank’ solution, where the ‘Good Bank’ takes all the assets with a steady cash flow, and can sustain itself with little capital injection. The ‘Bad Bank’ takes the rest of the assets that have deteriorated in value, and are subsidized to the extent that all liabilities are covered by Taxpayer’s money. The advantage is that now financial markets are aware of the status of each institution, and this may reduce credit risk (Blinder,2009).

The paradox of thrift: How a reduction in demand for funds requires fiscal policy to come to the fore

A deflationary spiral of reduced income, inflation and increased unemployment is a real threat at the moment. The problem is that the crisis has resulted in the deterioration of balance sheets of not only the financial sector, but households and firms as well. In the US for example, there has been a large increase in the household saving rate in response to a collapse in housing prices and the uncertainty of future income (Thoma, 2009).

Figure 11 Personal Saving rate for the US is on the rise

Thoma,2009

Another indication of a de-leveraging private sector is the demand for loanable funds in the US, by both small and large firms. This is another reason for the break in the linkage between HP money growth and the broad money supply, as a lack of borrowers tends to shrink the money supply.

Figure 12 US demand for funds is weak

Koo,2009

This weak demand for funds suggests that there will be insufficient consumption and private-sector (both residential and business) investment for quite some time. As the leakage generated from increased household savings and debt repayment exceeds the injection of new investment, the economy must adjust via reduced income. This holds particularly true in a world where interest rates are constrained by the 0 lower bound (Krugman, 2009).

Figure 13 Paradox of Thrift, Increased savings contracts the Economy

Krugman,2009

The return of Fiscal Stimulus: How it can mitigate the deflationary gap

When examining the use of Fiscal stimulus, one must first realize that its necessity derives from the inefficacy of monetary policy to deal with the deflationary gap. Given frictions in credit markets reducing the availability of funds, combined with a reduction in demand for funds, means there is an excess supply of desired savings (Krugman,2009).

Figure 14 Excess supply of desired savings at above equilibrium interest rate

Krugman,2009

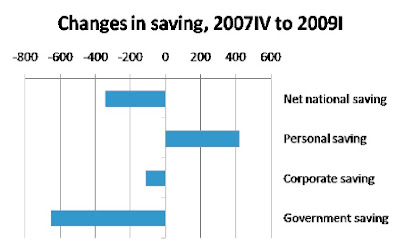

In the above diagram, the equilibrium interest rate i0 cannot be achieved due to the 0 lower nominal bound (Taylor rule gives i0=-5%). This excess desired savings, to not result in a deflationary spiral, must be offset by a reduction in Government savings. This has been occurring in the US, as well as other countries (Krugman,2009):

Figure 15 Government borrowing required to offset increased personal savings

Krugman,2009

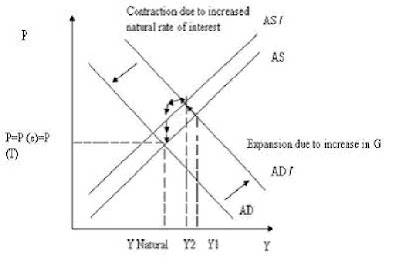

It is important to understand that the final effect of fiscal stimulus is dependent on its interaction with Monetary Policy. Looking at the Aggregate Demand/Supply (AD/AS) diagram, an increase in Government spending translates to a rightward shift of the AD curve. If at full employment, this will lead to increases in inflationary expectations, which shifts the AS curve up. As inflationary expectations are entrenched above an inflation target, the Central Bank responds by increasing the natural rate of interest, leading to a leftward shift of the AD curve and a return to the original equilibrium. The only change is that the increased government spending is offset by an equivalent reduction in private sector investment (which reduces due to the increased interest rates) (Blanchard,2007).

Blanchard, 2007

This analysis is simply not applicable in the current conditions, as the economy is NOT at full employment. Unemployment has increased up to 5% points in the US since the recession began.

Figure 17 Unemployment in the US is steadily increasing

Mankiw,2009

Even with a Central Bank committed to maintaining low inflation, at current we suffer from deflation risk. By implication, inflation will only return to a desirable level once the economy has reached its natural growth rate and is on its way to recovery. Thus the Central Bank will be accommodative for a long period of time. Measures such as flattening the yield curve imply the commitment of Central Banks to maintain a long-term structure of low interest rates. Accommodative Monetary Policy forms the backbone of effective fiscal stimulus, as can be seen by the IS-LM model.

Even with a Central Bank committed to maintaining low inflation, at current we suffer from deflation risk. By implication, inflation will only return to a desirable level once the economy has reached its natural growth rate and is on its way to recovery. Thus the Central Bank will be accommodative for a long period of time. Measures such as flattening the yield curve imply the commitment of Central Banks to maintain a long-term structure of low interest rates. Accommodative Monetary Policy forms the backbone of effective fiscal stimulus, as can be seen by the IS-LM model.Figure 18 Fiscal Policy very effective in a Liquidity trap

The above model shows how in a liquidity trap, the increased income from a fiscal stimulus (rightward shift of the IS curve), leads to an increase in money demand, which is satiated at a 0 interest rate. This accounts for the horizontal LM curve. To incorporate the concept of full employment, suppose the fiscal expansion is excessive. If it carries the economy beyond income at full employment, by implication, inflation will start increasing. This will cause Monetary policy to shift the LM curve up, (LM0 to LM1), to return economy to full employment. A lesson from this simplistic model is that it is better for the Government to have a large fiscal stimulus, rather than too little.

Dispelling the treasury view: Deficits do NOT raise interest rates under 'depression-like' conditions!

A corollary of accommodative Monetary Policy is that Budget deficits do not exert upward pressure on interest rates in current conditions. Both the Japanese ‘lost decade’ and current US recession show strong negative correlation between budget deficits and interest rates (Krugman,2009).

Figure 19 Japanese Budget Deficits coincide with reduced long-term bond rates

Koo,2009

Figure 20 US Budget Deficits coincide with reduced long-term bond rates

Krugman,2009

Fiscal policy is required to maintain money supply growth:

It has been noted that part of the reason for the inefficacy of Monetary Policy is the reduction in the demand for funds by de-leveraging households and firms in the US. If this reduction in demand for funds is not countered by increased government borrowing, the money supply will continue to shrink. Government borrowing from the Central Bank would increase the money supply as the Central Bank purchases treasury securities by injecting Reserves in Banks. On the other hand, if fiscal stimulus is financed by the Private sector, then Money supply will still increase, as by creating the incomes of workers in Government funded projects, the proceeds of Government spending will filter through to the Banking system and prop up the Money supply. This is evident in Japan (Koo,2008).

Figure 21 Japan’s Government Borrowing supported Money Supply growth

Koo,2009

By helping increase the money supply, it is helping to prop up the availability of funds to the private sector, and has indirect effects in terms of increasing the flow of funds and hence the velocity of money. Thus in a liquidity trap, Government spending can actually boost the money supply and hence Private Sector Investment. Japan’s ‘lost decade’ is an example of Fiscal policy maintaining money supply growth.

By helping increase the money supply, it is helping to prop up the availability of funds to the private sector, and has indirect effects in terms of increasing the flow of funds and hence the velocity of money. Thus in a liquidity trap, Government spending can actually boost the money supply and hence Private Sector Investment. Japan’s ‘lost decade’ is an example of Fiscal policy maintaining money supply growth.Japan's stop-go policy: how premature fiscal consolidation can lead to disaster

In 1997, Japan’s Prime Minister Hashimoto decided on a plan of fiscal consolidation, to reduce the 22 trillion yen deficit of 1996 by 15 trillion. The plan involved raising the consumption tax from 3% to 5%, increasing social security costs and shelving a supplementary budget (Koo, 2008). Instead of reducing the deficit, the economy shrunk for 5 consecutive quarters, and the deficit increased to 38 trillion in 1999. A deflationary spiral was induced, as Government deficits no longer countered the private sector’s de-leveraging.

This raises an important lesson, as it means the timing of fiscal consolidation is very crucial to the economic recovery. Given that Japan suffered from a corporate sector with insufficient demand for funds, fiscal consolidation should be practiced only when private sector investment is emerging.

Figure 22 Fiscal consolidation in 1997 led to a recession, reducing tax revenue and increasing future deficits

Another lesson is the notion of fiscal sustainability. A fair critique to fiscal stimulus is the debt burden imposed on future generations. The need to have a stream of budget surpluses in the future to pay off the debt is crucial. However, from the above example, receding Government spending now is not going to reduce the future debt burden, but actually increase it. With no fiscal stimulus, the deflationary spiral that ensues will cause income and hence tax revenue to contract, causing both budget deficits and an increase in the future debt burden.

Another lesson is the notion of fiscal sustainability. A fair critique to fiscal stimulus is the debt burden imposed on future generations. The need to have a stream of budget surpluses in the future to pay off the debt is crucial. However, from the above example, receding Government spending now is not going to reduce the future debt burden, but actually increase it. With no fiscal stimulus, the deflationary spiral that ensues will cause income and hence tax revenue to contract, causing both budget deficits and an increase in the future debt burden.The structure of fiscal stimulus: Government spending or Tax Cuts?

The first comparison one can make between Government spending and Tax Cuts are their respective multipliers. The Obama Administration, for example, believes their fiscal stimulus multipliers are 1.55 for Government purchases and 0.98-0.99 for tax cuts after 16 quarters. Government spending multipliers are always greater. The reason is simple; as Government spending has immediate 1st round effects of creating income, however tax cuts are contingent on the extent to which households consume.

Keynesian theory says the Government spending Multiplier

> Tax Cut Multiplier , where MPC is marginal propensity to consume, and t is the marginal tax rate. If we assume values of MPC=0.5, t=1/3, the ‘bang for buck’ (the increase in income per $ of future debt) is 3 for Government spending and only 1 for a tax cut, which shows that Government spending is better from a fiscal sustainability point of view (Krugman, 2008).

where MPC is marginal propensity to consume, and t is the marginal tax rate. If we assume values of MPC=0.5, t=1/3, the ‘bang for buck’ (the increase in income per $ of future debt) is 3 for Government spending and only 1 for a tax cut, which shows that Government spending is better from a fiscal sustainability point of view (Krugman, 2008).

Another comparison of Government spending and tax cuts refers to the notion of Ricardian Equivalence, which is the extent to which private sector savings increases in expectation of the future taxes required to finance the Government debt.

With tax cuts, it is crucial that they be permanent. If temporary, in the form of a tax rebate, then households are likely to save it in expectation of future increases in taxes, and partially because it does not reflect a permanent increase in their income. This was evident in the tax rebates in the US 2008 Stimulus package (Taylor, 2008).

Figure 23 Tax Rebate is fully saved in US, with no stimulatory effects on consumption

Taylor,2009

On the other hand, despite the increase in household savings, cash transfers to low-income households may be effective, in the sense that they are a group whose consumption will be depressed more and may have a higher MPC. Permanent tax cuts will avoid Ricardian Equivalence, however, it is impractical in the sense that taxes need to be raised in the future as part of fiscal consolidation.

On the other hand, despite the increase in household savings, cash transfers to low-income households may be effective, in the sense that they are a group whose consumption will be depressed more and may have a higher MPC. Permanent tax cuts will avoid Ricardian Equivalence, however, it is impractical in the sense that taxes need to be raised in the future as part of fiscal consolidation.

Let us look at Government spending. If a program requires $100B of government spending each year, consumers may save an amount equal, in present value, to the accumulated deficits, leading to an offsetting reduction in consumption. It is temporary government spending that avoids Ricardian equivalence, as

“…rational households would realise that the increase in their lifetime tax bills would be quite modest, which would imply a small reduction in consumption demand relative to the large increase in government purchases.”(Econospeak, 2009)

Some cite the incentive effects of tax cuts as a reason why tax cuts can lead to growth. There is little doubt that investment tax cuts, such as a cut in capital gains tax, company tax, tax rebates for innovation, a cut in payroll tax, do provide some impetus for investment and labour demand, effects not included in previous comparisons. A creative use of tax cuts, consistent with budget neutrality, are to enforce a permanent payroll tax (lowering cost of employing workers) with a gradual increase in fuel tax (Mankiw, 2009). The problem with supply-side tax cuts is that they may in fact have negative multiplier effects at the 0 lower bound! This is because of the deflationary pressure, which cannot be counteracted by nominal interest rates constrained by the 0 lower bound (Eggertsson, 2008).

This uncertainty of ‘incentive’ effects of tax cuts, coupled with Government Spending’s higher multipliers, accounts for why many countries around the World are having stimulus packages comprising a majority of Government spending. The limitation of Government spending is that there are only so many ‘shovel-ready’ projects, it is harder to implement and operates with a time lag, whereas tax cuts have immediate effect. Though Governments are likely to stimulate industries with excess unemployment (construction in the US), they should actively try to make their spending measures socially justifiable, to create a framework for private investment, and investing in key areas such as renewable energy, health and education.

Conclusion

After examining Monetary Policy, I conclude that we are in a liquidity trap situation, where conventional monetary policy loses traction, and frictions in credit markets disable the regular means of increasing the money supply. Given an insufficient demand for funds, and an excess supply of desired savings, it gives fiscal policy a mandate to dissave to restore equilibrium and prevent a deflationary spiral. It is necessary that Fiscal stimulus be temporary, and should only recede once the recovery is self-sustained by the Private Sector. The financial system must be restored to good health, and credit flows must return to normal levels. The policy-makers of the US and other countries are on the right track in trying to sustain demand, and will be able to avoid a 2nd Great Depression.

Oh god, so many graphs.

ReplyDeleteHi Ben, thanks for replying.

ReplyDeleteThere is never such thing as 'too many graphs' for an Economist.